At the sickle cell and thalassaemia screening support service, we frequently receive queries regarding antenatal screening results involving a raised level of Hb F, the fetal version of haemoglobin.

Haemoglobin (Hb) is the substance within red blood cells that carries oxygen around the body.

Thalassaemias is the name for a group of related conditions where the amount of haemoglobin that the body produces is reduced. This impacts on its oxygen-carrying capacity and can cause severe anaemia.

In an individual with sickle cell disease, the red blood cell becomes misshapen and rigid, resembling the shape of a sickle, when the haemoglobin is de-oxygenated (releases the oxygen to the organs). This process is called ‘sickling’ and causes a wide range of clinical complications.

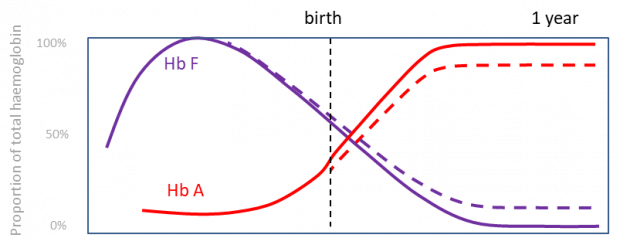

Hb F is the main haemoglobin found in the baby while in the womb. Levels then drop sharply after birth as Hb F is replaced by Hb A, the adult form of haemoglobin.

Most adults still make some fetal haemoglobin, but this typically accounts for less than 1% of their total haemoglobin. However, some people keep making higher levels of Hb F throughout their life. This is often termed hereditary persistence of fetal haemoglobin or HPFH for short. This can range from 1 to 100% Hb F for different people.

Hb F is a lot like Hb A. Adults who have no Hb A but can make enough Hb F are:

- generally physically well

- not at increased risk of having children with health problems

In fact, Hb F can be beneficial in many circumstances and is often found at higher levels when the body needs to make more red blood cells. For example, this can be during pregnancy or after an injury resulting in a lot of blood loss.

So why would an increase in Hb F during antenatal screening be anything to worry about?

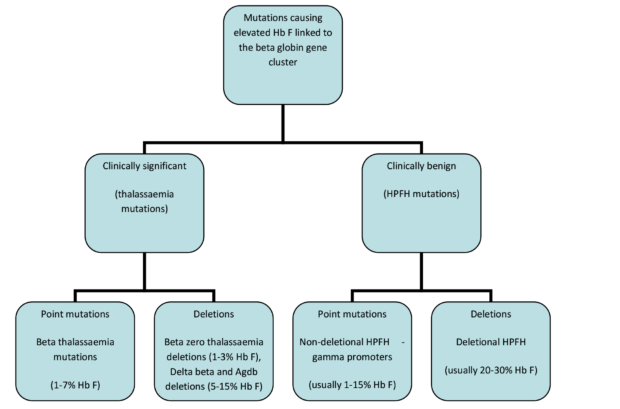

Well, an increased level of fetal haemoglobin is not a problem in itself. However, it is often an indication that there is a mutation in the beta globin gene region that changes the amount of the different haemoglobins being made. Some of these mutations are associated with significant health issues but others are not.

When follow-up is required and when it is not

So, when raised Hb F is identified during antenatal screening, what should happen next? Well, there are 4 scenarios to consider:

- If the level of Hb F is under 5%. The results can be reported as normal.

- If the level of Hb F is between 5 and 10% and the rest of the woman’s haemoglobinopathy screening results are normal. The results can again be reported as normal. As mentioned above, a small rise in Hb F is often seen in pregnant women. This is of little concern if there are no other issues.

- If the level of Hb F is between 5 and 10% and the lady’s red blood cells are paler than usual due to less haemoglobin being made. Follow-up is required. This is indicated by a mean cell haemoglobin (MCH) value of less than 27 on the full blood count results.

- A level of Hb F over 10%. This is more unusual and requires follow-up even if everything else is normal.

The women in scenarios 3 and 4 require follow-up because a small but significant minority could have a type of haemoglobin mutation known as delta beta thalassaemia. This does not affect the health of the woman assuming that she has no other mutations present in this region of her haemoglobinopathy genes. However, if the biological father of her baby also has a similar type of mutation – and if the baby inherits the mutations from both parents – the baby could develop a severe form of anaemia.

The father in scenarios 3 and 4 should therefore be offered haemoglobinopathy screening.

If his screening results are normal the couple can be reassured that their baby is not at significant risk of being affected by a haemoglobinopathy.

If the father’s results suggest he may have a mutation affecting the beta globin gene, then DNA testing should be offered to the couple to find out if they have mutations that could put them at higher risk of having an affected child. If they both do, they may choose to have the unborn child tested to see if the child is predicted to develop a severe haemoglobinopathy disorder.

If the father is not available for testing, the mother can be offered DNA testing to help establish if she has a mutation that might put the child at increased risk.

In some women, DNA testing may find that the increased level of Hb F is not caused by a delta beta thalassaemia but by a benign HPFH mutation that does not present any significant health risks to her or her baby. It is important that this information is noted and passed on to the team organising neonatal screening of the baby after birth. This is because the newborn screening results may be misleading if the baby inherits an HPFH mutation from one parent and a haemoglobinopathy mutation from the other parent. This could cause alarm and confusion.

Finally, if the woman’s full blood count is abnormal, do not forget to consider the possibility that the raised Hb F is a sign that the woman is suffering from a clinical condition which may require more care during her pregnancy.

For a more detailed version of this article download the Elevated HbF levels overview document from the Sickle cell and thalassaemia screening programme lab support service web page.

PHE Screening blogs

PHE Screening blogs provide up to date news from all NHS screening programmes. You can register to receive updates direct to your inbox, so there’s no need to keep checking for new blogs. If you have any questions about this blog article, or about population screening in England, please contact the PHE screening helpdesk.