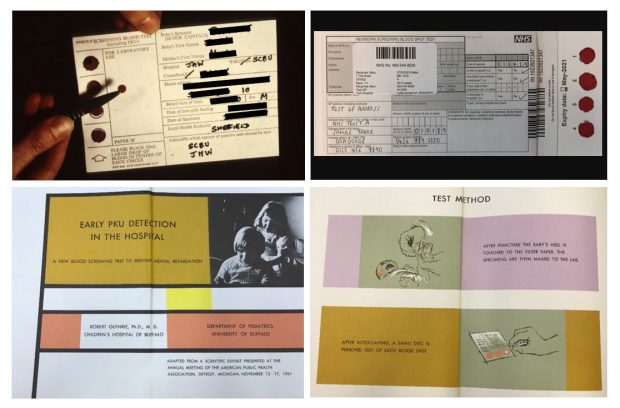

Bottom row: extracts from leaflet on ‘Early PKU detection in the hospital’ by Dr Robert Guthrie, 1961. Copyright: Birmingham Children's Hospital (except current blood spot card)

With all the modern advancements in screening, it’s easy to forget that some technologies have been with us for many years.

It's now 50 years since the introduction of UK-wide dried blood spot screening for phenylketonuria (PKU) in newborn babies.

In this, the first of a series of blog posts, we look back at how blood spot screening for PKU came about and how it paved the way for the expanded programme we recognise today.

We’ll share some fascinating insights from experts on how the programme has changed over the years and hear from a parent about their experience of PKU screening.

PKU

PKU is an inherited metabolic disease that affects a baby’s ability to break down the amino acid phenylalanine found in food and milk. This causes a toxic build-up of phenylalanine in the blood. Without early treatment, babies can develop brain damage, including serious learning difficulties. About 1 in 10,000 babies born in the UK has PKU.

PKU was the first metabolic disease known to cause irreversible developmental delay, and the first genetic disease for which a preventive treatment was available.

Early days of PKU screening

To begin our PKU story, we need to go back a little earlier than 50 years.

In the 1930s, developments in the understanding of PKU included identification of a musty odour and an unusual compound (phenylpyruvic acid) in patients’ urine.

By the late 1950s, this had led to development of the ‘Phenistix’ nappy test for PKU at 4 to 6 weeks of age. The test involved pressing a paper strip containing ferric chloride onto a wet nappy – if the strip turned a dark bluey green it was a positive result for PKU.

Following the first UK PKU conference in 1960, the Ministry of Health (as it was known back then) recommended that local authorities undertake routine screening of infants using the Phenistix test.

However, the test was difficult to carry out, could miss the condition in its early stages, and did not always detect mild cases.

It was also known that the treatment (which was still being developed) was most effective if given as early as possible, long before signs and symptoms of the condition appear.

This prompted a re-think.

The dried blood spot test

Enter Dr Robert Guthrie. Dr Guthrie was an American microbiologist who had a niece with PKU. In 1960 he developed the dried blood spot test (also known as the heel prick test) as a way of screening all babies for PKU shortly after birth.

The test was simple, sensitive (able to correctly detect babies with the condition) and inexpensive, and used a blood sample collected from a baby’s heel onto a special filter paper. The sample could be collected easily, dried and sent to a laboratory for testing. Importantly, the dried blood spot test could be carried out much earlier than the Phenistix test.

Following a further government recommendation, screening for PKU using Guthrie’s blood spot test was introduced as a national programme in the UK from 1969.

Treatment for PKU

A low-phenylalanine diet was first proposed as a treatment for PKU in the 1930s. However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that a method for preparing such a diet clinically was realised.

Sheila Jones, a 17-month-old showing signs of untreated PKU, came to the attention of Dr John Gerrard, a paediatrician at Birmingham Children’s Hospital (BCH) and Dr Horst Bickel, who was doing his PhD at BCH, in 1951. Bickel had an interest in amino acids and suggested using the urine-based PKU test (ferric chloride) for BCH patients with developmental delay.

They tested Sheila for PKU and found that she had the disorder. Persuaded by Sheila’s mother, they accepted the challenge of trying to treat her by producing a diet. Along with the biochemist Dr Evelyn Hickmans at BCH and help from Dr Louis Woolf at Great Ormond Street Hospital, they produced a home-made, phenylalanine-free feed for Sheila to take.

The feed tasted very bitter but was effective, and Sheila showed improvement. After a time, Bickel added a small amount of phenylalanine back into the feed to prevent weight loss and maintain growth.

Sadly, due to a combination of circumstances, Sheila was only on the diet for a further 3 years and her development regressed again. However, her story paved the way for the screening and treatment of PKU that we know today.

A screening pathway

Following the switch to dried blood spot screening in 1969, the national programme went from strength to strength. By 1974, 98% of infants were screened in the newborn period and only 5 of 357 PKU cases identified between 1974 and 1978 were diagnosed after 3 months of age.

There was also greater emphasis on links between screening, diagnostic and clinical services to support families and achieve a high standard of care across the pathway.

Proposed safeguards mentioned in a 1981 British Medical Journal paper include reporting of all negative results, checking the birth register for untested infants and providing advice for travellers or those moving into the country – all things that we are still working on today!

The screening programme today

In 2016 to 2017, nearly 780,000 babies were screened for PKU in the UK, and over 100 babies were screen-positive and referred to specialist care.

In addition, nearly 1,400 babies screened positive for one of the other 8 conditions introduced to the programme over the last few decades – all benefiting from the same dried blood spot technology and efforts to join up services to achieve the best possible outcomes.

Living with PKU

As we reflect on 50 years of dried blood spot screening for PKU, it’s important to remember that screening and diagnosis is only the beginning for children and families affected by this condition.

There is no cure and a life-long diet is recommended. Although the treatment prevents the devastating effects of the condition, there are many practical, social and psychological impacts to living with PKU. Women with PKU also report difficult experiences relating to pre-conception, pregnancy and postnatal care.

We would like to acknowledge the achievements of the UK National Society for PKU, which helps and supports those affected, and champions accessible and high-quality care for all.

More to come

It's now 50 years since the introduction of UK-wide dried blood spot screening for phenylketonuria (PKU) in newborn babies. To celebrate the landmark, we will be publishing a series of articles looking at how blood spot screening for PKU came about and how it paved the way for the expanded programme we recognise today. Look out for our next post tomorrow.

PHE Screening blog

The PHE Screening blog provides up to date news from all NHS screening programmes. You can register to receive updates direct to your inbox, so there’s no need to keep checking for new blogs. If you have any questions about this blog article, or about population screening in England, please contact the PHE screening helpdesk.